10 Great Westerns

By no means, would I claim to be any sort of western afficinado, however, I do, from time to time, intermittently enjoy the stylized genre. “Western,” as a moniker, I feel-should rather be a starting point than determinative, for in the very least, the film industry has greatly expanded what’s possible within its stratification. Colloquially, it seems like most folks associate such memetic images of the ‘wild west’ or cowboys when they think western, even though nowadays, there’s a whole sub-genre (or two) belonging to the concept of neo-westerns, i.e. No Country for Old Men, or El Camino. While I’d prefer to not try my pedestrian knowledge at the subject, I preface for sake of explaining what kind of western I’m thinking for the following list.

Sans #1, there won’t be modernity (though filmmaking techniques, styles, etc. don’t count) with technology on this list, except-of course, six shooters or firearms belonging to the late 1800’s. While I’m open to genre-bending within a fictitious, semi-historical setting, what these following films all have in common are their hybridized aesthetics: desert, heat, silent standoffs, revolver-heavy gunplay, rampant alcoholism, jangling coins, gold bars, poker, horses, outlaws, hyper-masculinity contextualized by a near-metaphorical if-Freudian relationships with guns, an at-times shallow subtext and/or problematic imagery (which, I’ll say: the genre is not without its insidious origins), jingoism, and, just about enough women to convince us that we aren’t watching a planet inhabited solely by spurned revengers packing ammo.

Neo-westerns and what other evolutions of the genre will be left for perhaps another list. In closing, I don’t claim these are the best per se, but, rather, just some of my favorites.

Without further ado:

#1. Walker (1987)

Written by Rudy Wurlitzer

One of my favorite films irrespective of genre, Walker is such a loud movie in terms of subject matter, that it breaks glass as it plays. What kind of western is this, exactly? Some say this is but a satricial film with a western backdrop, others label it a subgenre of “acid western,” adjoining the great Alex Cox to the likes of Alejandro Jodorowski or Jim Jarmusch. In certain ways, Walker is an indictment of the entire genre, not so much an anti-imperalist film but billet doux for victims and dissenters of Western aggression. One could say this movie encompasses a host of styles, as by its very nature, Walker, outside its subject matter, is a hybrid-western, no-it’s a thoroughly postmodern dissertation, or wait, maybe black comedy, or at odd-times, a soberingly depressing – albeit fictitious, to varying degrees – visual essay? There isn’t a succint writeup to account for what this film tries to do, and I’d argue, does exceedingly well. Whether or not to the detriment of this film (which, I’d say the opposite), Cox’s use of intentionally jarring, explicit anachronisms is but one of many tools Walker employs to tell its message. Based on the real-life of William Walker – an American solder of fortune who invaded Nicaragua circa 1856, overthrowing the government in a coup d'etat – to some degree, Walker doesn’t so much subvert the subject as it runs away with it. The Clash’s Joe Strummer provides an amazing soundtrack to boot, of which, along with the film’s production, all was shot in Grenada at the height of the Contra War. For a long time, this picture was blacklisted and out of print, though Criterion has of April 2022, finally rerelased the infamous film on bluray. As for this film’s overt anti-empire messaging, legend has it that it was directly because of this movie which lead its director becoming blacklisted from Hollywood. Walker is one of my favorite movies, ever, and has left a powerful impact in me since.

#2. Cemetary Without Crosses (or, Une corde…un colte… -1969)

Written by Robert Hossein, scenario by Dario Argento and Claude Desailly

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the term, ‘spaghetti western’, it’s essentially a sub-genre within westerns to designate a period beginning in the 1960’s, which involved Italian productions and filmmakers giving their takes on the western (often, with quite a stylization unequivocal compared to American films). Cemetary Without Crosses isn’t perhaps the greatest western ever made, but it’s one of my favorites for many reasons. Director Robert Hossein, a neophyte to the genre, who dedicated this film to director, Sergio Leone, was something of an anomaly: Hossein was an accomplished stage actor back in his native France, and had a prolific filmography as a director, but nothing under his belt to be thought as par for the course. The demarcation of Hossein’s experiences behind the lens (in-comparison his contemporaries) only served to justify some of the stylistic subversions within Cemetary Without Crosses. Yes, there’s long standoffs, orchestral bravado superimposed atop desolate tears, gunsmoke, squinting into the sun, you name it, but it’s done in such a way with this film that feels uniquely memorable. Famed Italian giallo director Dario Argento, also had a hand in the script (credited for scenario), which lends the plot itself to a sort of palpable, borderline-dancing-on-gothic-macabre territory. While you won’t be left flabbergasted by this movie, what it does leave you with is an engrossing, entertaining, stylized ride you won’t forget.

#3. Once Upon a Time in the West (or, C'era una volta il West – 1968)

Written by Sergio Donati and Sergio Leone, story by Dario Argento, Sergio Leone, and Bernardo Bertolucci

Some consider this to be the finest film within the genre, for which I wouldn’t necessarily differ. Clocking in at a hearty 2 hours, 45 minutes (theatrical cut), Once Upon a Time in the West is a vertible epic no matter how you slice it. Like a good majority of westerns, this film’s themes and plot aren’t perhaps the most profound, but are texturized and executed in such a way, it begs us to engage with its apotheosis of poetic, outlaw mythology by muzzle flash. Accordances, truces, betrayals, love bordering on hate, survival and psychopathy are colors of this film’s spectrum, where we follow a tale lost but for a widow and three very different men. The talented Henry Fonda plays against cast here, where his soft-eyed glance of blue vulnerability works so well inversed as the villainous, “Frank.” Long after you’ve seen this movie, there linger so many moments unforgettable, seared into your cognizance, such as the hyper-visualized opening sequence, complete with brilliant foley, sound effects and impressive score…or a shootout heralded by the bloodthirsty Fonda, who, armed with a piece of iron, aggrandizes himself through gunsmoke.

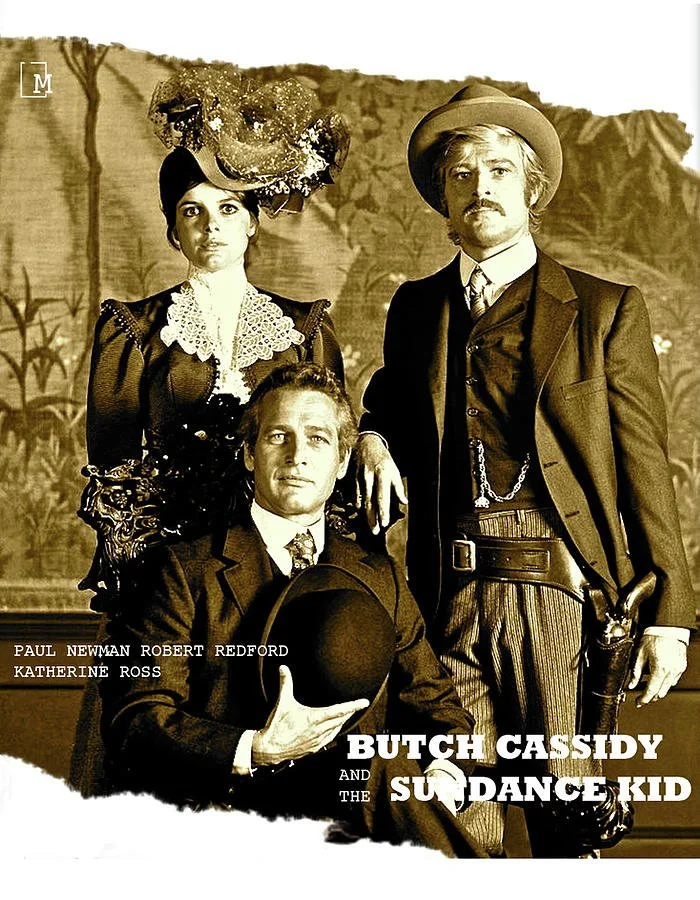

#4. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

Written by William Goldman

Of all the non-spaghetti westerns, this might be my favorite, though for reasons (I feel) not particularly associated to its praise. The direction, I feel, is unrepresentative to the film’s strengths. There’s a straightforward, directive vision for the script which feels undynamic against its writing and acting, which I feel, strangely, gives this movie a sense of tonal levity; Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid appeals to our desires which feel conclusively unsophisticated, both in subject matter and subtextual analysis (beyond what’s incarnate to westerns as a genre), for the film celebrates the ways we idolize antiheroes, and does so (I’d argue) in a traditionally populist, folksy tone (minues, of course, the Hollywood-industrial complex). Maybe not heady compared to other westerns, but I just think there’s something beautiful about the thought of Butch and the Kid on the run whilst traveling the world, experiencing a hidden story to themselves amidst Europe, separated from circumstances that made them infamous…just, the feeling of a story untold (which we see only through a montage of photos, something I wished had been a different film altogether: their on-the-run menagerie betwixt existential encumbrance) struck a chord. For me, perhaps the film’s most hated scene – i.e. Raindrops Fallin’ On My Head – was, as sacrilege as it sounds, my favorite, serving as an encapsulation of the feeling I loved about this movie. Also, Robert Redford will forever remind of young Revolver Ocelot (ala’, The Phantom Pain), but, I love that too.

#5. The Harder They Fall (2021)

Written by Jeymes Samuel and Boaz Yakin

I love, love this movie. There’s not often an event where I feel compelled to either talk to the screen or yell from excitement, but Netflix’s recent The Harder They Fall, made me in spades, provoking a kind of ‘movie magic’ awe in me. Director Jeymes Samuel does so much right, from purposefully tongue-in-cheek subversion of expectation and racial coding (in many ways, meta-textual), to playfully artistic imbedding of contemporaneous, cultural symmetries into the past’s zeitgeist. From the moment it starts until its actual-twist-of-an-ending, The Harder They Fall feels like an injection of sapid, hedonistic filmmaking into a genre wrought of endless droning, for which it plays with conventions associated to exploitation, blaxplotation, action-comedy, hip-hop, drama and even a bit of music video. Apart its festive direction, the acting throughout The Harder They Fall withstands the temptation to play it too ‘winking-at-the-audience’, too ‘we’re all in on the same joke’ routine, but tracks with bonafide emotional highs and lows. Idris Elba is just a force of nature with whatever he does, dictating the flow of emotion feels only perfect, even despite the fact he doesn’t have nearly enough screen time (for me). Also, the line, “lightning with the blam-blams” continues to live on as one of my favorite movie lines of any film.

#6. My Name Is Nobody (or, Il mio nome è Nessuno – 1973)

Written by Sergio Leone, Fulvio Morselli and Ernesto Gastaldi

My Name Is Nobody has strange locution: a western intermixed of comedy yet earnest drama throughout. The great Peter Fonda also appears in this film, but it’s more of the standard, wise, elder-patriarchal figure he’s associated. Though I wasn’t surprised of his characterization this time around, nevertheless I found Fonda’s emotional conjecture through those eyes to carry weight, adding to an already interesting pretense: “Jack Beauregard,” a tired and old gunslinger of yesteryear, catches the fancies of gun-toting impulsive, “Nobody,” who soon riles the aged gunman out of retirement by constantly challenging him. Throughout their father and son-ish rivalry, the plot unfolds, involving revengeance of siblings, laundered profits through a mine, grief and ultimately, providence. As per many on this list, the legendary Ennio Morricone scores this unique hodgepodge of drama meets a laughing bullet, providing the kind of score you’d expect from the spaghetti western virtuoso. Relevantly, this film would be the last of its kind to feature Fonda, adding to its already bittersweet and memorable of an ending.

#7. A Fistful of Dollars (or, Per uno pugno di dollari - 1964)

Story by Adriano Bolzoni, Víctor Andrés Catena and Sergio Leone, dialogue by Mark Lowell, written by Víctor Andrés Catena, Sergio Leone and Jaime Comas Gil

Essentially a spaghetti western retelling of director Akira Kurosawa’s 1961 samurai classic, Yojimbo, A Fistful of Dollars stands on its own as more of a reimagining than genre-bending remake. Yes, that Clint Eastwod works it well as “Joe,” or more commonly known as The Man Without a Name (in reference to the Dollars trilogy). To watch this movie without any prior knowledge of the genre’s conventions, might paint all disagreements of the late 1800’s west as silent standoffs amid sun-invoked squinting, sweat over poor makeup, and various foley to accentuate the homoerotic tension. The precedence set by director Sergio Leone would subsequently influence so many after; they say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and A Fistful of Dollars singlehandedly sparked an emulsification of the petri dish of films to follow, for perhaps every action movie that came after was somehow indebted to this movie’s sensibilities, which are a sublimation of: stay with the tension, for as long as humanly possible, wait until a flea’s cough could trigger the domino fall, and, make every dude look as dispassionately excised of joy as possible, with as little words phrased, all talking done through the blaze of gunfire.

#8. Ravenous (1999)

Written by Ted Griffin

Ok, think about this: horror-western? Not a neo-western-horror (i.e. the cult classic, From Dusk Till Dawn), but more of The O.K. Corral meets Freddy Krueger (or, something like that)? Well, if that doesn’t tickle your fancy, then perhaps nothing will! …joking! Okay! So, Ravenous fits the western bill by taking place not long after the Mexican-American War, our hero a disgraced US officer, “Boyd,” who’s sent in-punishment to an exiled post named Fort Spencer, and after his arrival, a mysterious string of deaths soon follow. There’s a few standout performances, from the always-solid Guy Pierce as our lead, the great Jeremy Davies as “Toffler,” and Robert Mr. Trainspotting-Begbie-himself-Carlyle, who absolutely nails it as “Ives/Colqhoun.” Although there isn’t a spectacular array of gunfights and saloon fisticuffs, nor is Ravenous’s plot anything to write home about, the way in which it executes its primary motif of melding historical trope with (then) modern horror feels so…cool? I wouldn’t go on a limb to say this is a scary movie in the purest sense, but what its mood lends is an overall sensibility towards a cult-film buff’s palette, and sure enough, Ravenous since its release, has gained recognition as a decent film.

#9. Stagecoach (1939)

Story by Ernest Haycox, written by Dudley Nichols

Yes, we’re not going to dissect a lot here, because some of Stagecoach’s images deserve their own bonafide writeup, however, on the merit of plainsay writing, direction and acting, this is another caliber. Yes, this film was accredited to J. Wayne’s meteoric rise in the industry, but I thought he was fine considering the film’s strongpoints consist of artfully juggling its plot across 9 different characters, each with their own trajectory. Director John Ford, who’s yey another that could be written about, succeeded in accomplishing one facet that would live long after his retirement: cementing Monument Valley to be synonmous with not only the southwest, but westerns in of themselves. Having the privilege of visiting the sacred site years ago, I can say there was perhaps a lot of historical leaps the filmmaker took with turning Monument Valley into the proverbial backdrop of seemingly all westerns, but I digress. Beyond this Golden Age film’s obsoleteness, therein lies a categorical strength to its vision, for it feels ahead of the curve, preliminary modern, consummate as to how to write a screenplay.

#10. The Hateful 8 (2015)

Written by Quentin Tarantino

If you’ve ever wanted to reimagine John Carpenter’s The Thing melded with a pastiche and exploitative, western-era Resevoir Dogs, then look no further. Something of a departure for writer and director Tarantino, The Hateful 8 is a reintroduction of newer conventions onto older style, so much so that there were times I forgot I was supposed to be watching a western. All of the ingredients are right here, from the Ennio Morricone original score, to the excellent cinematography by Robert Richardson, top-notch acting from the likes of Kurt Russel, Samuel L. Jackson, Michael Madsen and more, the recipe just works. Upon its initial release, I had the pleasure of watching this in theatres, and though perhaps not floored, nevertheless Tarantino’s take of a traditional formula fell in-line to his other films: an unforgettable romp. Indeed, recent era Q.T. seems evolutionary, consistently shifting amid genres, yet he’s still managed to remain a recalescent presence in cinema. The Hateful 8 craftily surmises humor over a juxtapositioned tensity of violent absurdness, and its that interesting space, filmmakers like the Coens, Paul Thomas Anderson and Tarantino paint with their depth.