10 of My Favorite Films

Films are interesting. Is their primary purpose is to entertain, to enlighten, perhaps explore? Commercial, big-budget/studio features are certainly a matter of profit and return-of-investment, but even then, some of those films leave powerful impressions on their intended audience. I believe the commodification of art is an all-different conversation, and what artistic merits of film are axiomatic, irrespective of economic philosophy. Anything and everything can be art, even films devoid of soul, corporatized or contrived and assembled purely for financial-means, and sometimes can linger in our minds.

I enjoy a lot of different movies. Camp to pastiche, schlock, mellow-drama, noir to neo-noir, slashers, rom-com’s, period pieces, (in certain cases) exploitation, martial arts are all fair game on any given day. I’ll spend the rest of my life watching movies-I hope, and there’s different reasons for why I may love a film; each and every movie I like, I do for various reasons, and there’s really no one authoritative rubric or ethos I grade them with. Sometimes, a film’s seemingly-vacuous nature may charm me, while others, the opposite. The beauty about the nature of subjectivity is coming to our own conclusions and experiences to comprise our taste.

It’s fun to make these.

#1. Y Tu Mamá También (2001)

Written by Alfonso and Carlos Cuarón

My favorite film of all time. This film is a road trip film, sexuality, coming-of-age, grief, poverty, existentialism, youth and life. A touching and moving film, Y Tu Mama Tambien tells the story of two best friends who embark on a road trip with an older woman, yet, there’s so much more at the heart of this movie. The narrative slips in and out of lucidity, blooming with profound carnal vignettes and confessions, poetic sondering, a slice of life that doesn’t insist its message but breathes it, lives and depicts it through visual beauty. I can’t say enough about the impact this movie had on me, but I savor my re-watches when I’m in the need to cry, or be inspired.

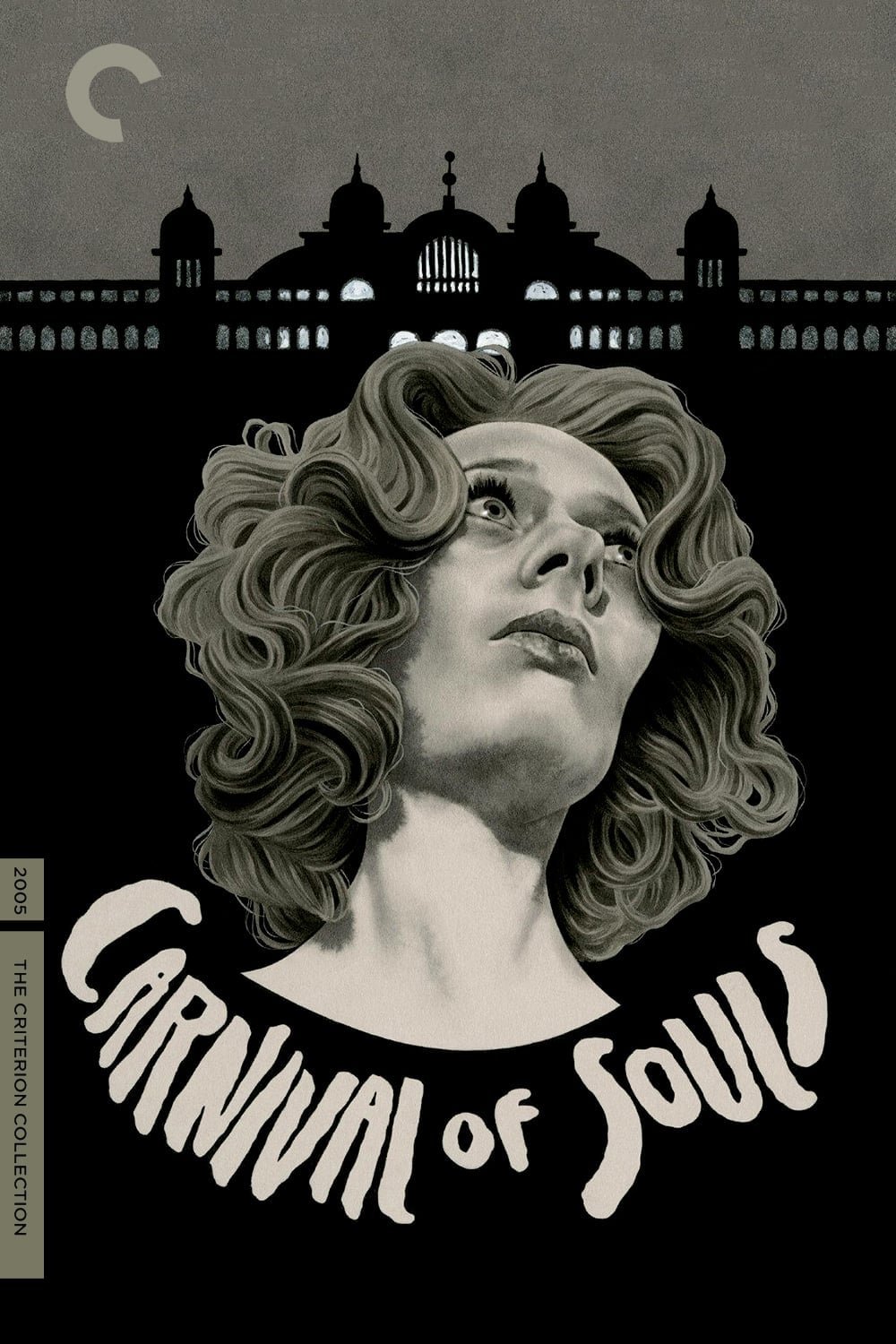

#2. Carnival of Souls (1962)

Written by John Clifford, story by Herk Harvey

The greatest B-movie of all time. Carnival of Souls teeters upon greatness, and is such a good piece of honest, emotional, raw-filmmaking, that it transcends its own limitations. Of course, there is camp, at-times stilted acting, dated filmographic convention, but there’s also a genuine expression of mythos, a surreal if-oddly juxtapositioned mysticism ever-present throughout its short runtime, a haunting, strangely beautiful soundtrack that’s exclusively made of pipe organ. I think this film says a lot on its surface as well as its subtextual implications, and I have my own theory that Carnival of Souls is an extended metaphor of a woman struggling with her sexuality.

#3. The Breakfast Club (1985)

Written by John Hughes

I will never not be over this movie, even though it was before my time. Inspiring countless other films to follow in its wake, The Breakfast Club essentializes the rules for teenage-angst films and writes the playbook. What makes this movie still everlasting is how we start with what we see as stereotypes, archetypical facades of each character, then see them explore how they both resent yet identify with their labels, attempting to deconstruct their assigned-aesthetics within a pseudo-therapeutic catharsis. Another magic part about this movie is the age of when it was made, capturing a snapshot of 1980’s indulgence, innocence and ignorance. This movie is far from perfect, but something about the spirit within it is totally, Saturday Mornings Forever.

#4. Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Written by Stanley Kubrick and Frederic Raphael

What are dreams, things that happen in our subconscious, or conscious fantasies that pervade our daydreams? Is there something greater underneath it all, or are we, at the end of the day, just a large group of under-sexed, unhappily married, mammals? Eyes Wide Shut takes it upon itself to play around with said questions, all in the form of a psycho-sexual thriller. For me, this is the best Stanley Kubrick film, and it feels like a greatest hits or amalgamation of his entire body of work. There’s no clear answers given in this movie, and what conclusions to deduce are fickle given that, Eyes Wide Shut doesn’t make the “realness” of its plot pertinent to tell a story. I like to think this film is about class, and how the escapades of society’s petty-bourgeoisie are ultimately unknowing, myopic, occult fever-dreams that are a parallel reality to our own.

#5. Spice World (1997)

Written by the Spice Girls, Kim Fuller and Jamie Curtis

Yes, this movie is the best. Underneath Spice World’s bubblegum veneer and pop-cultural-fanfare is an almost heady-subversive satire of genre films, and no, I don’t mean that tongue-in-cheek. Spice World is a product of its time, dually a band-on-the-run film similar to A Hard Day’s Night, as it a commentary of itself, a self-actualized satirization about the inherent banality of commercial exploitation. Sure, there’s ridiculous, over-the-top plot “twists” and beats, a nonsensical continuation of story without reasonable pretense for suspending our disbelief, but I truly believe this film does so knowingly; Spice World knows the territory as well as itself, why it exists, and the futility in attempting to make itself something other than what it wants. Girl Power!

#6. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

Written by Joseph Delteil and Carl Theodore Dryer

Tied with Cecil B. DeMille’s Carmen as my favorite silent film, The Passion of Joan of Arc is a beautiful and moving piece of early filmmaking. Its message, heroine, vignettes, pans, angles, lighting, script, acting, emotion, all parts are perfectly contained but robust in of themselves. A story about as timeless as its legend, the film’s namesake is depicted throughout her infamous trial and subsequent martyrdom. I wouldn’t consider this a religious film by any means, despite that the movie goes to bat for themes of faith and belief; I would consider The Passion of Joan of Arc to be a movie about love, about the power of belief, conviction, non-conformity, the soul of a young girl standing up to external power. This is a story of humanity and inhumanity as much as it’s about a higher power and sectarianism, making me cry every time.

#7. Days of Heaven (1978)

Written by Terrence Malick

This movie left a heavy impact on me, imprinting in my mind long after. Days of Heaven follows three urban vagabonds who embark on a cross-continental journey and land on a small Texas range, sharecropping for a wealthy landowner. The themes of this movie are all realized and self-evident amidst the plot: surrogate family, poverty, memories, life’s transience, youth, love and lust. What sticks with me is Linda Manz’s narration, how her being and character mimics a seedling, flowing from one reality to the next, how beautiful her archetype is constructed, how she’s a survivor of a small, transient page of anonymous history, to which she recounts her time of near-heavenly bliss living rich for a short moment, only to be lost to time.

#8. Breathless (1960)

Written by Jean-Luc Godard

I’ve done a writeup for this that can be found here. Funny, beautiful, crude, poetic, edifying and indulgent, Breathless gives as much as it takes. I can get lost in this film, admire what I see, how it does what it can on-screen. Are we awake if we live our lives as if a dream, or are we asleep if we live our life as reality? I’m infinitely inspired by this movie, to create and experience what I feel is important to me, because how it’s made. Breathless at-times, left me just that.

#9. Ghost in the Shell (1995)

Based on the manga by Shirow Masamune, screenplay written by Kazunori Itô

In my opinion, Ghost in the Shell is the pinnacle of Japanese animation, even in light of other powerhouse films like Akira or Princess Mononoke. The future depicted here is grim and fully cyberpunk, reminiscent of the tech-noir film Blade Runner. What line between cyborg and human is blurred, life itself is no longer a simple metric, and the Tokyo we see surrounding the characters appears devoid of centrality. Does our sentience determine the capacity for humanness, or is it foundational within our emotions? There’s quite a bit of (welcome) existential and philosophical meandering throughout Ghost in the Shell, but it doesn’t feel needless or preachy. What we do find is a texturized though austere world where the questions are more important than their answers.

#10. Halloween (1978)

Written by Debra Hill and John Carpenter

Halloween is the one and only movie that’s ever truly frightened me. This film had the unfortunate success to help create the onslaught of copycat slasher flicks, but there’s a lot more to this movie than cheap thrills, jump scares, excess gore or whatnot. To me, most of John Carpenter’s early work has this “feel” that I can’t quite describe, but Halloween encapsulates the dark and lingering moodiness so prevalent in his filmography. Ghosts, monsters, the paranormal don’t do it for me, but Halloween’s antagonist is a goulash of the otherworldly and primal, a bogey but a man in a mask, the commixture of our childhood fears manifested. The plot while simple, can be viewed as a metaphor for class-consciousness or suburban racism, among other things. Later rereleases of this film destroyed the ambiance/tonality by intercutting additional unreleased footage of the “gore shots,” which completely take me out of it. What makes Halloween scary is what you don’t see, the implication, tension in shadow. If you haven’t ever seen this movie, do yourself a favor and make sure to watch the original theatrical cut; nothing of value is lost with any of the additional footage.