Remembering: “8 1/2 (1963)”

Preface: I have a lot to say about this film, so this writeup will be longer than most.

Regarded by some as one of the first of its kind, perhaps even single-handedly creating the genre of mockumentary, Federico Fellini’s 8 1/2 has, with lingering viscidity, withstood the test of time. Released in 1963, the Italian surrealist film, something of both a comedy and arthouse drama, garnered acclaim and recognition for its poesy, radical and essayish departures from the prevailing orthodoxy of its contemporaries, including direction, subject matter, aestheticized subversion of expectation, and if-didactic exploration of avant-garde expression. Fellini’s vision and frankness sublimates the screen in hedonistic confessional, for the director’s avatar as our protagonist serves to encapsulate and manifest a most profound unspokeness within, making this film a kind of unabashed, self-conscientious, thwartedly-aware, laconic if self-satirized form of surrealist diary mixed self-aggrandizing-and-effacing portrait of flawed posterity, decorum, and bordering-on-narcissistic-though-wholly-relatable-self-idolized-grandeur.

In plain English, 8 1/2 as a film alone, feels like it’s about one-too-many things to succinctly put into coherent stratification (though I’ll try): finding one’s passion, examining our muses, then in a step further, examining how we examine our observations, invoking an epodic transliteration of Goddard-esque magical realism, though-dually, as if contrition, putting our imperatives on trial through industrialized criticism...for 8 1/2 is somehow, a film about a man making a film about making a film. We begin from a dream within the mind of our fictionalized yet not-too-far-from-reality protagonist, a youthful though aging director, “Guido Anselmi” (amazingly played by Marcello Mastroianni), who, upon waking, finds himself in lachrymose self-exile for reasons both health and artistically-centered. On throughout his journey, we follow his stream-of-consciousness, where his imperiled flights away from reasonableness detether into surrealist vignettes, most of which get provoked by linear abstractions of any given woman he lusts, for we find the director is not only a chauvinist womanizer, but even perhaps sex-addicted, or in the very least, a maladaptive daydreamer (or if you’d prefer, an artist in the throes of brainstorming).

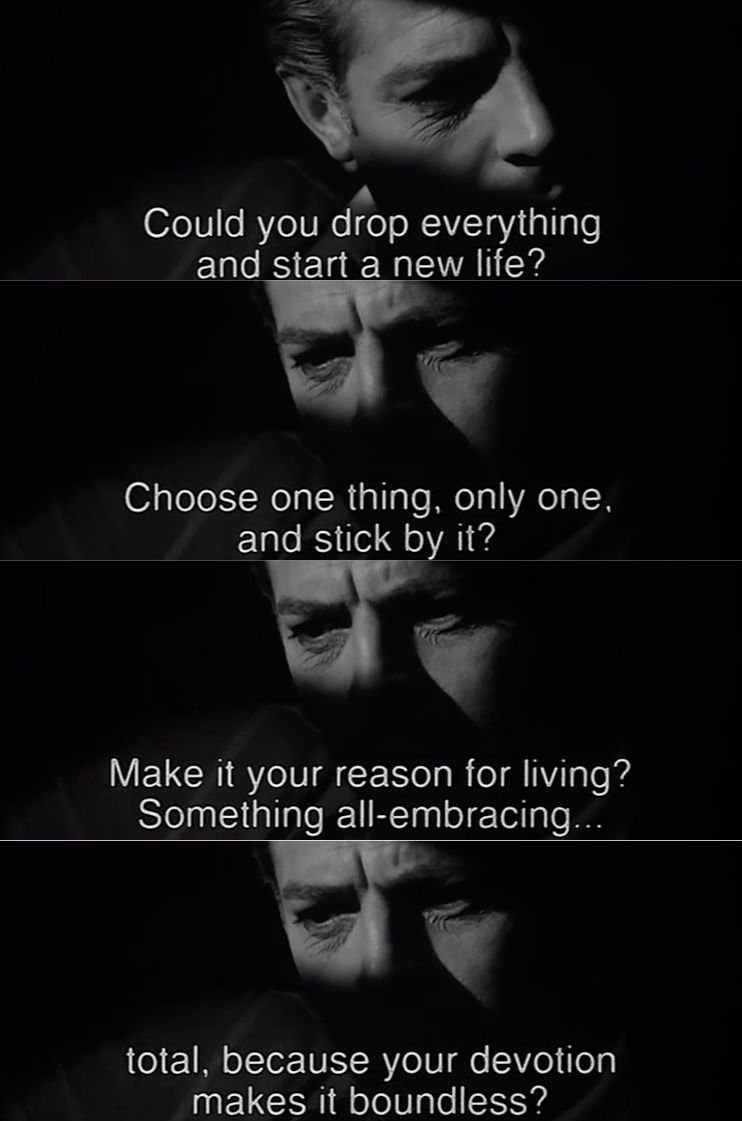

8 1/2’s protagonist, “Guido,” verbalizing the echoes amidst his creativity.

If we simply follow the plot, 8 1/2 makes enough sense, being we are simply watching a film about an Inception-worthy, ‘movie-within-a-movie-within-etc.’ premise, though what some might have seen isn’t enough to encapsulate the film’s many parallel, repetitious, and dueling theses. What if, the things we were most ashamed, the things which made us vulnerable, also yet, inspired us without rival? What if, the way we liked to see ourselves, though knowing it is but different from reality, ironically, drove us into self-examination? Fellini plays with the idea of an ouroboros here, an apotheosis of cognitive self-cannibalization, for our protagonist fuels creativity by indulgence, self-examination by ways of impulsivity, delusions of grandeur out of self-hatred, and it is in this complex interplay between reality and fantasy, do we find an almost insultingly simple and profound brevity within 8 1/2, to which, I was not only engaged, if-mesmerized, but hypnogogically hypnotized by its cadence and rhythm.

Guido flaunts his flirtatious concupiscence amid whirling excursions of various women through his life, some in-present, some as body-doubles for what enables his remembrances, to which he giddily exceeds the narrative and sonders in and out of the moment and into whatever he sees, thinks or feels is the next escape. Representationally, the women we see symbolize quite a few different concepts here, from virility, fertility, fading youth, embodiments of infantilism and/or emasculation, morality, aestheticism, to even – in the case of “Luisa,” our protagonist’s complex and somewhat-estranged wife – creativity itself, the latter to which, marriage is given breadth by an apt metaphor to the relationship one has to their ‘spark’, i.e. creative passion. At a surface glance, 8 1/2 might come off insincere with its resplendent, regal set-pieces, designs and choreography, for the mind of Fellini seems inscrutably banal as it is of sophisticated beauty, though I’d argue the faults of our protagonist are but most purposeful; “Guido,” as a character, serves in the same way we interpret “Charlie Kaufman” in Adaptation, or “Rick” in Knight of Cups, i.e., a deeply troubled, hypocritical addict to excitement, much as the cost of not only their likeability, relatability, but furthermore, their humanity (and even inversing that, what flaws that are exaggerated also, yet, somehow, humanize them conversely...).

In some sense, 8 1/2 is as much a film about filmmaking as it is about the person making it, or rather, their flawed, vulnerable conscientiousness of their creative process. If you’ve ever seen David Lynch’s 2001, Mulholland Drive, then perhaps, sans the thriller-horror aspects, you might feel familiar to the thought that everything is not what it appears. Another popular film I think can serve to form some relational basis and comparison is Vanilla Sky, and though I wouldn’t go on to recommend it, the parallels and allegories are there (e.g. everything is a dream within yet another dream, and so forth). Yes, there are very obvious odes, lamentations, and nods to the greater filmmaking apparatus as a whole in 8 1/2, and the feelings of Fellini are most definitely felt for sure, but I’d say in context specifically to this film, the business-of-a-movie-plotline is there to simply hang the more abstract, deeply subjective and convoluted abstractions atop it, and though most contemporary filmgoers might write this one off as pretentious, perhaps even detrimentally-indulgent, I’d say this feels like a screenwriters film more than a director-centric one, even as blasphemous as that may come off. There’s an internal dialogue and rhythm here that sings truly to the inner myopic in all us writers, all us hopeless romantics/neurotics who try to no-avail of escaping through our art, and all of the guilt which we hear in the back of our mind finds its way onscreen through the mouth of our comedically adroit, though insightful critic.

ROSELLA: I don’t know what she wants. She’s lost. One day she says one thing, and the next day something else. Unfortunately, I think the only thing she’d like is for you to be different.

GUIDO: Why?

ROSELLA: It’s the mistake we all make.

GUIDO: Is that gentle fellow courting her? Is he in love with her?

ROSELLA: You’d like that, wouldn’t you? No more guilty conscience. You’re such a scoundrel. Poor Enrico. He’s so clumsy at it that everyone’s noticed. He hangs around her, listens to her, keeps her company. He’s a wonderful friend.

GUIDO: I thought my ideas were so clear. I wanted to make an honest film. No lies whatsoever. I thought I had something so simple to say. Something useful to everybody. A film to help bury forever all the dead things we carry around inside. Instead, it’s me who lacks the courage to bury anything at all. Now I’m utterly confused with this tower on my hands. I wonder why things turned out this way. Where did I lose my way? I really have nothing to say, but I want to say it anyway.

In the above exchange, we find Guido discussing the subject of his dispirited wife’s potential attractions to her best friend, “Rosella,” (in her words, his “Jiminy Cricket”) and it’s here that I feel compelled to compile my inferences about what the subplot regarding our protagonist and his estranged wife means on a symbolic level. For I, Luisa served as the heart and anchor of the story in a fundamental way, if we are taking into account the basic story (which on its own, already feels compelling), though I’d say what particularly struck me of their relationship was not only their continual back-and-forth-rapport, but what it represented: Luisa is Guido’s muse, literally and metaphorically. What we can deduce of her presence in his life is multilayered; Guido, at opening, must spend time away from his wife and fantasize about other women, for he, in his own twisted “reality” logic, feels compelled to lust for beauty as a way to reconnect his carnal desires back to his wife, and in that way by itself, does the allegory make sense of Luisa equals muse, but there’s more to it. We can see some of this when she watches the various screen tests, mired by vexation while smoking a cigarette, as if to judge the rough drafts of other ideas while holding onto the idea she has of her husband, and her pain is but also, the pain of seeing your work in-progress and hating it, doubting your vision, and so forth.

Guido’s remonstrances about whatever perceived lusts Luisa feels for other men, is, in a way, his inner voice of his work, his passion, and when Guido begins producing his soon-to-be-film, Luisa’s feeling sway in and out from adoration to beguilement, as if, in some sense, serving as the writer’s instincts when losing control of their voice in-collaboration with others. Guido can’t stand her, but he lives for her, and when he imagines her within his sexual fantasies, then as an adulated and submissive, archetypical housewife near the end of the film, we find that Guido is beginning to deconstruct his own indulgences, recognizing (in a gorgeous, stage play-like shot of her scrubbing floors) that what he loves about her is what he cannot tame, the same way he feels his flaws and delusions should fuel him, rather than hinder. I know it’s a lot to take apart without sounding incoherent myself, but I truly felt magnetized by how strongly Fellini took to shape Luisa’s role as the copacetic emotionality present with every artist when they “fall in love” with a project (or in the film’s case, fall out of love, then back in on the outset).

Guido questions his sincerity, though conversely, feels compelled by an inner animus though flawed and addicted to daydreams. His vulgar confessional, much drawn to an allegorical relationship we see him attempting to sway with papal authorities, are representative of his self-admirement and self-criticism; the Catholics, and critic, serve to underscore Guido’s attempts to express himself without constraint, allegorically (and literally) representational to industry, while his officious jester, and menagerie of various motherly figures soothe his childlike inhibitions he has beneath the surface, for he is both, callous and indifferent, as he is romantic and idealistic.

CRITIC: Frankly, I wish I could have offered a word of advice. But now I understand that you are trying to solve a problem for which there is no solution, to find clearly defined faces for a crowd of characters who in your script are so rough so vague, so ephemeral – [...] Listen to this. “The solitary ego that revolves around itself and feeds only upon itself finally chokes on a great cry or a great laugh.” Stendhal wrote that during his stay in Italy. If we’d only read those sayings on chocolate wrappers sometimes, we’d be spared many an illusion.

Guido’s elaborate set piece of a skeleton of a soon-to-be-rocket-apparatus wholly works to further reinforce the idea of Fellini, that budgetary constraints, special FX, production and the politick of film are but placeholders for what really makes a film, and that is, an irrevocable and fervent emotion or joie de vivre about what our compulsions manifest. The suits, the studio bigwigs all love to see his grand construction, but on throughout the film’s entirety, Guido is stuck chasing his own dreams, sentience, and the fancied admirations of whatever woman has caught his desire, and in that sense, does 8 1/2 further provide a sentiment to the status quo.

CRITIC: If we can’t have everything, nothingness is true perfection. Forgive me for making all these references, but we critics do what we can. Our true mission is to sweep away the thousands of miscarriages that try every day, obscenely, to come into this world. And you would actually leave behind you a whole film, like a cripple [sic] leaving behind his crooked footprint. What monstrous presumption to think that others could benefit from the squalid catalog of your mistakes. What do you gain by stringing together the tattered pieces of your life, your vague memories, the faces of those you never could love?

Near the end of the film, the critic’s summations regarding our director’s work encapsulates what we can infer of Fellini’s own approbations of himself, and in that sense, Fellini feels as if to say he recognizes the importance, the strength in self-criticism and listening to our most ardent detractors (which, aptly, are often ourselves) while seeing the profundity and truthfulness in their at-times cynicism. Fellini here feels as if to say, through the mouth of the critic, that he is resigned to be never able to make the type of film he sees in his own head, for doing that would superimpose the responsibility of an artist to their audience. Conversely, however, I felt a sense that Fellini was also saying, that this critical voice will always see the wrong in our ways and will always shoot down whatever freedom we attempt to gain from creative expression, so it is our duty to listen with an open ear, but never take it more than a grain of salt, as if, to always listen to our inner critic would amount to never creating anything in the first place.

GUIDO: What is this sudden happiness that makes me tremble that gives me strength and life? Forgive me, sweet creatures. I didn’t understand. I didn’t understand. I didn’t know. How right it is to accept you, love you. And how simple. Luise, I feel like I’ve been set free. Everything seems so good, so meaningful. Everything is true. I wish I could explain, but I don’t know how. Now everything’s all confused once again, like it was before. But this confusion is me, as I am, not as I’d like to be. I’m no longer afraid of telling the truth about what I don’t know, what I’m looking for, what I haven’t found. Only this way do I feel alive. Only this way can I look into your faithful eyes without shame. Life is a celebration. Let’s live it together. That’s all I can say, Luisa, to you or the others. Accept me for what I am, if you can. It’s the only way we might find each other.

LUISA: I don’t know if what you’ve said is right, but I can try if you help me.

In this sequence near the end of the film, I believe Fellini offers his most verbalized form of what 8 1/2 is achieving to do: a self-portrait of a flawed man, to which, we also see him through his own fragmented eyes, including the distortions of his perception. This finality to which our protagonist meets his wife is, in a way, a reunification of artist and muse, creator and creativity, and in some faint symbolism, filmmaker and audience. Sometimes, after we finish a project, it can feel like there’s a field of wanting within ourselves, for the imperious desire begins once more to find our inspiration. Luisa decides to accept her husband in all of his addictions and flaws, for which, he redempts by finally admitting what he is, and that is, a vulnerable person, to which, I found myself relating, thinking maybe, perhaps, aren’t we all? And, at the end of the day, isn’t everything or rather, anything we decide to create, tinged of our own indulgences and inherent biases, childhood memories, daydreams, ambitions, sexual fantasies, etc., to which, are those elements about our human sapience that we should deny rather than converse?